More’s Utopia was designed from the outset to stay in the sphere of ou-topos [no-place] and ou-chronos [no-time]. Plethon’s utopia fervently[2] searches for locality and temporality […] From a Christian and Stoic viewpoint [such insistence] confirms that by nature man is unable to find happiness in his Dasein and is attracted to what he does not or is not allowed to possess. The sense of dissatisfaction is history’s hidden lever, the draw of the impossible is all-powerful, future felicity becomes the phantom of the opera pulling the strings from the backstage of history. Plethon suffered from the alchemist’s fervor.

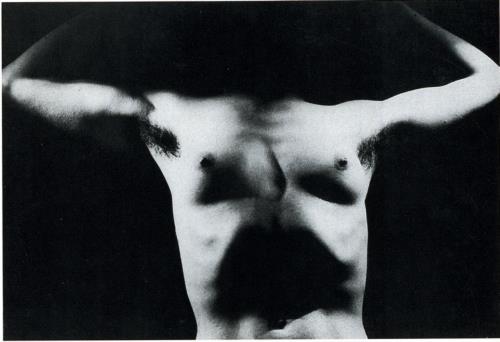

Fiction engineering calls for a practical approach: find a clever angle and run with it, limiting aims and designs, using things we already know. It’s a good approach. Still, some never learn, I guess, and want to have all the angles. Some go out of their way to slam and synthesize as many aspects of their reality into their word-thing, ending up with scraps of a dozen stories that still wouldn’t add up to one. These people are happy to be lost, enamored with hide-and-seek and the play of shadows, secretly content to be mapping the territory in anticipation of their fatal rendezvous with its bull-headed lord.

[1] Handy link to Siniossoglou’s expansive thesis on Plethon, as opposed to the lovely book of essays I stab at translating.

[2] The word is ‘αγωνία’, which at a glance maps to ‘agony’ in the English but then also acquires properties of torment; I go with ‘fervor’ to stick to the New Greek meaning of intense, overbearing anticipation, although chances are if you go through the one, you also go through the other.