Near the end of this year’s Daredevil (that’s season 3 if you come from the future), Matt gets asked something you wouldn’t expect his knuckle-bruising services to deliver: he gets asked to “Forgive us”.

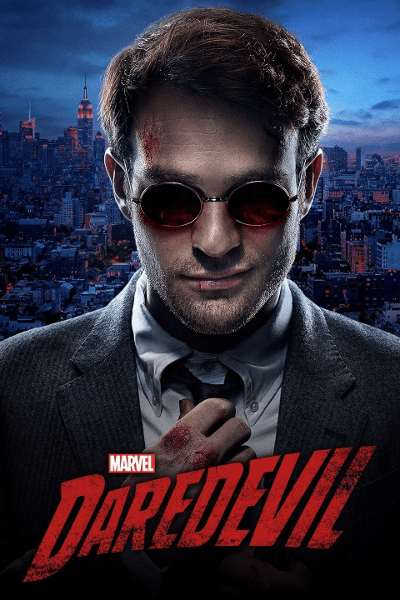

Of course Daredevil the show has a prominent Christian component. And of course superheroes, like the harrower of hell, deliver salvation. But the series also throws its weight on Matt’s secret identity as a shadow, a persona most commonly known as “the Devil of Hell’s Kitchen”, or plainer still: “the Devil”. In promotional material, Charlie Cox even greeted us with a mischievous smirk. Sadly, we don’t see much of that side of his Matt Murdock, whose default state is the wallow. The journey begins in the confession booth, his motive force the paradox of guilt: feels bad the law won’t let him do enough good, feels bad for taking matters into own hands. Ergo, the worse Matt feels, the more mobs he ends up kicking in the face.

(And boy was season 1 a roundhouse bonanza.)

This Daredevil is halfway between the Batman and the Punisher; conscious his vigilantism is led by a broken moral compass but not so broken himself as to let rip unto murderous rampage. Season 3 puts him on a redemption/self-actualization arc, wherein, as per pop-psych manual, he needs to learn to forgive in order to overcome his fear of intimacy in order to come to terms with his Daredevil persona, i.e. kick people in the face in a more self-assured fashion. This chimes nicely with all of us who were weaned on superheroes partly because the stories were giving voice, costume, and superpowers to a shadow part of ourselves that yearned to break out of ego hell. Pop psych manual, in a perhaps Jungian flavor, says you-as-Matt work towards absorbing your shadow and resolving your hang-ups into a productive synergy.

Arcs apart, what emerges is this interesting idea of the forgiving (i.e. saving) devil, of the superhero as a strange hybrid of the Anointed and the Deceiver. Could we see our shadow not just as something to parley with but as an active agent of dark becoming? The rundown alleys of rough justice leading up to the Kingdom, retribution meeting absolution. Superman might save us with a smile and a wink; perhaps there’s a Daredevil who does so with an evil smirk.

It’s not a call for Satanist superheroes, at least not in the Do That Thou Wilt sense, as they wouldn’t be interested in salvation. (For that matter neither would an antihero in the mold of John Constantine, though he has the initials.) It’s that self-actualization arcs aren’t all they’re cranked up to be and the hero’s journey needs to take us somewhere new.

Star Wars and the Matrix didn’t really help us out of ego hell. In fact it’s more likely they helped us rearrange it into cozily perverse fantasy castles, where escape isn’t any more desirable than a backpacker’s wish of a more authentic life picking grapes in rural Spain. If the Force can lead our hero to a fulfilled life where he gets to happily do the often mundane work of love day in day out, good for them; we still like to imagine ourselves levitating the remote and beckoning our way out of parking tickets.

This easily extends into politics. After all, the same shadow part used to whisper: why can’t we sometimes break the rules for the sake of the rules, kill or silence only those who deserve it, do bad for good? The paradoxical space of vigilante justice has of course been deconstructed, castigated, and flipped on its head more times than a show seal, the point well defeated, but we still transpose our ideological struggles on blockbuster cinema, almost making the box office a battlefield of souls. It’s kind of a shame then the thinkiest of caped crusaders only go so far as middle-managing the status quo and its dirty laundry.

Consider Daradevil: Is not killing the parasitic Kingpin really the ethical choice? Daredevil walks the old tightrope: Thou shalt not kill and become the Kingpin at any cost, because the kernel of liberalism is vanquishing our foes with our identities left intact, so we’ll just pretend sticks ricocheting off temples might not cause permanent cerebral damage. In the end, even his comrades don’t seem very confident about his creative high road / middle road solution. Is the tightrope too well-worn? (Fittingly, given Disney’s odd recent decisions, the journey that started with the paradox of guilt might well end with the dead end of forgiveness.)

Subjects for further research: Big Narrative Media might be an expression of the consumption ethos (Buy That Thou Wilt; Will That You’re Bought) but the multiplex still gave us a decent V (the only Anointed Deceiver figure I can come up with). Here’s hoping the old story, be it the hero’s journey or the superhero genre, has life beyond regurgitating its own continuity. We could use someone properly new, someone who links the Shepherd to the Butcher, who gives us a space where we inhabit our shadow and not vice versa, who explodes the tightrope metaphor in the bargain. Perhaps someone we shouldn’t assume has come to bring peace.

[All the essays here.]