After the sea took me I washed up wrecked on the island of the unnamable woman. Hogs were running about rolling in the mud squealing. She waited for me at the entrance of her hut.

I see her now, holding her arms in her black gown and staring dead blank at me. Even at this distance her eyes are omens. And then her hair this black curly mass.

She took me in and draped me in thick wool and set with me by the fire. I thanked her and asked no questions about the pigs or my bowl of chow. She asked if there was a woman in my life. I said no, and what about her. Her face stiffened. My chest seized a little but I kept chewing and swallowing.

Finally she smiled, and I felt then how thick and hearty the stew was and smiled back. I remembered suddenly I had a soul and my bones now aching tired. I laid back on my elbow and listened to the fire.

Her face across the hearth snapped me back into the moment. I found tears in my eyes, and something new in hers. A thing I might have called… pity, once? In a previous life or something like that.

I spent my days walking around and helping with the pigs. There was much I didn’t remember and I kept busy as a way to keep the thoughts running without me having to watch over them. She gave me rubber boots and some mismatched menswear she said was just lying around. I stomped around the mud awkwardly with the hogs grunting around me fussing for no reason. They would roll around with each other sniff and complain and have little nothing fights. Then I poured the slop from the sack I was carrying into the trough and watched it slur out in a fall and land noisily into itself. The pigs gave up all activity and rushed hungrily towards me squealing hard. My shoulder communicated a relieved warmth.

She was watching me from the far side of the fence, sat on a stool with a piglet in her arms. She stroked him under the chin with her fingertips, and around the chubby ears that would move about teased and ingratiated. I went over and sat with. A little smile was dancing on her face.

We watched the feeding for a spell. Then I said what I was on my mind.

“Why did you do it?”

She kept looking on and maybe sighed though she didn’t let me hear it.

“We were lonely. We wanted you to play with us.”

I thought about it, tried to comprehend it. I couldn’t.

She passed me the piglet, balancing the start of his belly on her one hand. I took it carefully and pressed it to my chest. I held it and it was quiet.

With her other hand she offered a knife.

We looked hard into each other’s eyes, then I took the knife and slit the piglet’s throat tracing the line behind the jawbone. I didn’t know I knew how to do that. The creature squealed out its life in confusion and sorrow.

Was that my childhood finally over? My hands bloodied, my quarry embraced?

“There’s someone you need to meet,” she said.

My heart seized in terror. “Entomo–“

“No,” she stopped me. “The one from beyond the mirror.”

There was much I didn’t remember but I knew I needed a boat. I walked around her shores and always found her watching me from the distance. I thought it better not to wave.

There on the shores many marooned little vessels. Small and not all of them wrecked, as if the seamen came here in small missions. I had known not to ask about the pigs but I would not recall why. I seemed to be moving by instinct as if that’s the only thing I had left in me.

“Do you even know where you’re going?” she asked while I was affixing the sail of my chosen dinghy. “What’s the point of the beating seas? Why go round and round in circles?”

I thought for a moment and finally said: “So coming back always feels new.” I said it but didn’t believe it, didn’t understand it. She wasn’t satisfied, but I kept hammering on.

When the day came I loaded up the hold with clayfuls of freshwater and salted pork. I thanked her again and stood there on the shores with her holding her arms black gown and all. I had nothing to do about her melancholy. She had nothing to do about my sorrow.

“I wish you well,” I finally told her, and meant it. She made no reply so I boarded and looked up and away at the gathering night. Would my star still be on the sky?

Then she said:

“Στράτο.”

I turned to her:

“You could have never been one of us.”

I let it sink in. It really was a compliment. But I felt a line coming on after a very long time and I had to say it:

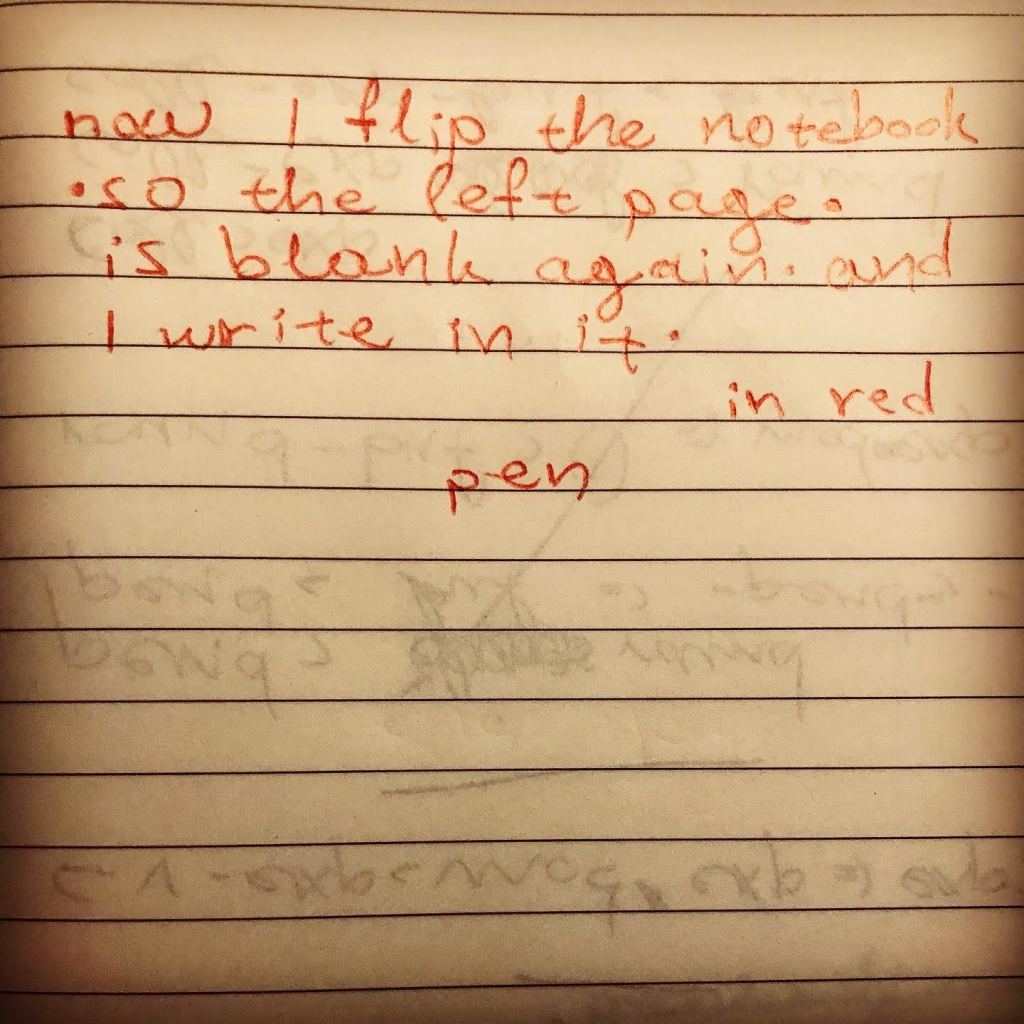

“I promise to be funny again.”